CHINESE TAKEOUT

by George Jenne

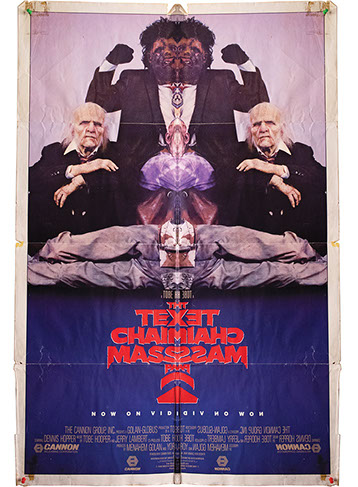

Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2 is awkward and unshapely, like a turd squeezed out of a few meager nutrients. Even to the undiscerning eyes of the pubescent boys that the movie aimed to please, it’s silly. It lacks the raw power of the original film. Still, I watched it almost weekly, as one of those teenagers. It made me giddy. I was energized by its blunt humor and the way it shamelessly touted Grand Guignol violence. Fakery for the sake of spectacle.

During the days that Chainsaw 2 was in big on my mind, I worked with an older woman named Marisa, crafting fish models for a zoologist in ghostly quiet, downtown Durham. It was the closest I could come to the cinematic fakery that I held dear. The work was numbingly tedious, and Marisa curtailed the monotony, for both of us, with fits of expose’. She fed me tidbits about her adult life, instigating brief, flirtatious engagements that peppered the day, serving them up with disarming nonchalance, taking long drags from her cigarette.

She blew smoke rings through a plume of epoxy vapor when she told me that she had dressed the sets for Chainsaw 2. She suddenly radiated an aura of essential wisdom. She knew the ingredients of that funny little turd that would greet me when I got home, half way inserted into the VCR. I probed for details, but she wouldn’t quite say what went into its making. Instead she talked about how she and her husband, who was the assistant art director on the movie, were joined at the hip such that, at the end of a typical fourteen hour day, she would slip into their bathroom, hoping to render just one squeak of solitude, only for him to follow right behind her, whip it out and say, “Be outa your hair in a sec, babe. But first, get ready for that deep sound.”

In the movie, Dennis Hopper plays a tightly wound, Texas Ranger, named Lefty Enright who stalks the murderous Sawyer family into their lair under an abandoned amusement park. Once, on that set, Marisa had to repaint the bottom of a wall that was designed to burst open with a cache’ of human guts. Hopper was waiting on the sideline to kick the wall open for the camera. Marisa hunkered into a low squat, moving a hair dryer back and forth across the wet paint. After watching her for a few minutes, Hopper leaned in, unnervingly close, and whispered in her ear, “I can smell your pussy.”

Marisa conveyed the story with the deadpan of a low burp. I grinned as if I could smell it in the air. She shrugged, twisted her lips, then returned to smearing epoxy onto a giant block of foam, shaped like a deep sea fish.

I felt teased. Marisa knew my love for that movie and my reverence for Dennis Hopper. She had reflected every hint of my own naiveté back on me, with this single story. The longstanding question: Is he really an asshole, or is he just that good? The abrupt answer: Yes. And no.

For me, Hopper’s best character is Frank Booth, in Blue Velvet. There, Hopper exerts a double layer of menace. It’s not enough that Frank is a violent psychopath. He’s also a needling asshole. This makes him all the more terrifying, as he swings between hot rage and petty irritation. “Heineken? Fuck that shit! Pabst! Blue! Ribbon!” That line, which is by far the movie’s most memorable, conjures a nervous laugh and primes us for the true depth of Frank’s unholy darkness.

There’s a shooting script for Blue Velvet floating around that suggests that Frank rapes the voyeuristic innocent, Jeffery Beaumont, after threatening to send him a “love letter,” Frank’s euphemism for a bullet to the brain. The implied rape doesn’t make it onto film, but if you know the script, and you watch the movie, deep humiliation percolates during the corresponding moment where Jeffery wakes up in a puddle of mud, stripped down to his boxers, his chest remarkably supple and hairless. “He did it,” you think. “It really happened.”

Here’s another mythic tidbit: The prerequisite gas that Frank huffs to gear up for acts of violence was originally helium. So, when he squealed, “Baby wants to fuck!” at Isabella Rossellini’s character, Dorothy Vallens, he actually sounded like a baby that wanted to fuck. Apparently, this went badly during shooting. Brutal as it is, who could keep a straight face when listening to what sounded like a squealing balloon guide Isabella Rossellini through her own rape? Lynch himself says that when Hopper lobbied for the role, he told Lynch that he had to play Frank because he was Frank. We’ve all heard stories about what blow-hards method actors are, but as far I can tell, the evidence says Hopper’s plea was the real deal. Consider Freddie Jones’ helium squawk in Wild at Heart, which corroborates that Lynch was into the sound of tiny voices. Check that off as a truth, then pair it with Dennis Hopper’s general track record for drug use and bad behavior, and suddenly Marisa’s tale of bizarro misogyny rests well inside a circumference of believability. He is an asshole. He’s not that good.

I gobbled every tidbit Marisa gave me. And I told myself that these were only titillating stories of the “seven degrees” type that are handed down from a guy that knew a girl that had a cousin that worked on a porno that used the same gaffer whose ex was personal assistant to Kevin Bacon. It’s just part of the sordid myth of entertainment culture, which spins right around into an even murkier burlesque of American culture. As such, it’s basically noise - each time, a different version of the same slander. So I continued to grasp hopelessly at the conviction, like Jeffery Beaumont does in Blue Velvet, that there must still be some kernel of decency in people.

Marisa was a single mom who sought refuge in North Carolina after fleeing Los Angeles when her husband cheated on her while shooting another film. She was pregnant, so she sat that one out, and it was the first time they had not worked together. The first time she wasn’t cornered in her own bathroom.

She discovered the deceit while riding shotgun in her husband’s van, on the way to pick up an order of Chinese takeout. She saw the greasy film of a footprint on the windshield, just above the dash, and when she measured her own foot against it, out of simple curiosity, she was stunned to see that the sizes did not at all match.

Again, her incredulity barely registered when she told me. The forensics alone are maddening; the ghost of a footprint reveals itself when the California sun hits the windshield just right! But what burned me up most, was that she portrayed a Zen of acceptance at stumbling into this gruelingly unexpected fold in time and space. As usual, I watched her soldier past the memory and right back into her work, while I seethed for her.

Our boss at the model shop, was a nerdy and ebullient man, meaning, he could be deeply irritating. So it was no surprise to me when Marisa exploded at him. He was clumsy with her, in the way that a nine year old boy has to strain all sensibility to successfully interact with the opposite sex. Marisa freaked. Over what, I don’t quite know, except that I heard our boss say something about his ears not being able to register the screeching pitch of Marisa’s voice. She grabbed her gear and stormed out the door, while he looked to me, flapping his arms in defeat.

I saw Marisa only once after she walked off the job. She lived with her son in a cheap, brick apartment across from the Harris Teeter. I dropped by after work and drank a beer on her couch while she put the boy to bed. A portrait of her loomed on the opposite wall. It was painted by her ex-husband. He had depicted her topless. Her lower abdominal muscles strained a studded leather thong. I imagined he thought he was Frank Frazetta rendering Valeria, Conan the Barbarian’s battle buddy and concubine. I sat longer than I should have, and I drank more than I wanted, because I missed Marisa. But I also needed time to absorb the image. I was embarrassed for her, for being depicted this way and for hanging it in her living room, 3000 miles away from her ex. Had she not escaped after all? Yet, the display of such an insult was honest. It looked like a poster for one of the bad movies she and her husband had worked on. The key piece of an unresolved story line. A third act summation of all of the shit she had eaten. So, I kept an eye on the painting, while Marisa delicately tipped her beer and casually disclosed more intimacies in steady advance. I hung on her every word, glancing at the painting. Glancing back at her. The two of them watched me from opposite sides of the room. I was scared shitless for whichever asshole was next.